Bill C-11 has been on a lot of minds since it passed Parliament and became law last spring. Also called the Online Streaming Act, it promises enhanced discoverability opportunities for Canadian content creators on platforms like YouTube, Spotify and Netflix.

But in order for these platform’s new algorithms to recommend Canadian content, they need to be told which creators are, in fact, Canadian. This is where provenance metadata comes into play.

Let’s break down what provenance metadata is, why it matters and how you can incorporate it into your digital presence.

Data about the data

Metadata literally means “data about the data.” Simply put, it provides descriptive information about a “thing”, like a person, organization or creative work.

Let’s take an artist bio on their website. The artist themself would be the “data”, while the descriptive information would be their first and last names, photo, notable works, social media links, and so on. But in order for this descriptive information to be true “metadata,” it can’t simply be human-readable text on a webpage. It must also be structured in a way that machines can understand when they read the code on that webpage.

We’ll come back to machine-readable data later on. For now, let’s focus on what provenance metadata is, specifically.

There are many different types of metadata. Provenance metadata belongs to a larger family called “descriptive metadata”. This type describes the content of a piece of data –– as opposed to its format, date of creation/modification, copyright status, etc. For more information, see Section 1.2 of État des lieux sur les métadonnées relatives aux contenus culturels (Observatoire de la culture et des communications du Québec, 2017).

Origin, history and location

Provenance metadata refers to information about origin, history and location. In the case of an individual artist, this might include:

- Their place of birth

- The place(s) where they grew up

- The place where they currently live

- The place where they work

- A place associated with the origin of their parent(s) or ancestor(s)

- A place that the person identifies with, either on the basis of cultural affiliation or of a sense of belonging to the land

Provenance metadata can also be expressed at different levels of granularity: neighbourhood, city, region, province, country, traditional territory. More granular is not always better. For example, because birthplace is personal information, some artists may hesitate to disclose it at the city level. However, if given the option to share their province of birth, they may feel more comfortable disclosing it.

Provenance metadata isn’t just relevant for artists. It can also describe important information about artistic organizations, cultural venues and creative works, such as:

- The address of a performing arts company

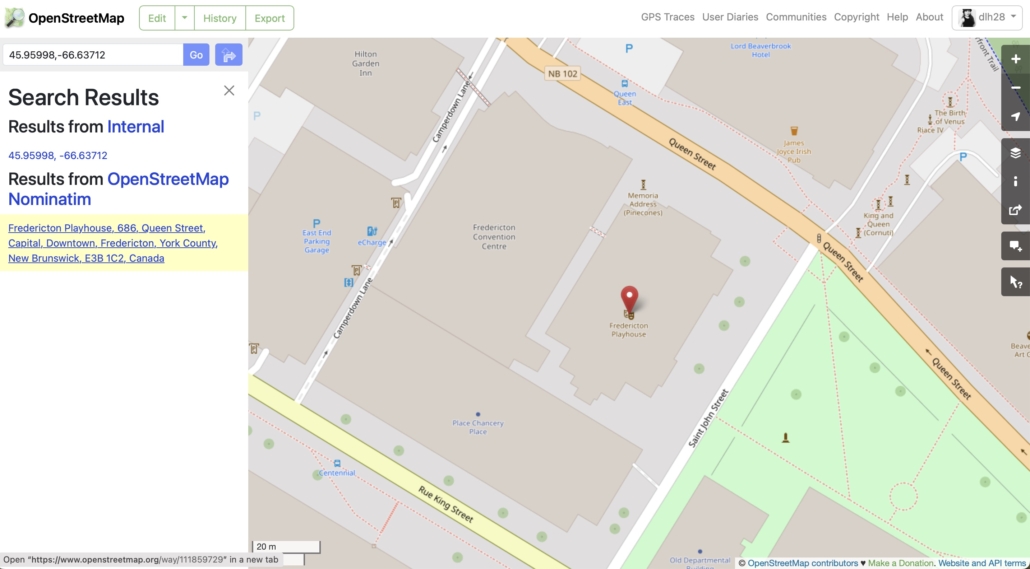

- The latitude and longitude coordinates of a performing arts building

- The filming location of a music video or other live performance recording

- The (real-life) geographical setting of a play or other performance work

Spoken/written/signed languages and the many expressions of Indigenous identities (including affiliations to nations, bands, etc.) are also highly relevant distinctive traits about an artist. However, to keep it simple, this blog post will focus on the general geographical types of provenance metadata. Future posts will devote attention to metadata about language, and metadata about Indigenous artists and arts organizations.

Disambiguating (similar) names

Beyond adding key bits of geographical information, provenance metadata is a powerful tool for disambiguation. In other words, it can tell robots that one online entity is different from another online entity with a similar name.

Let’s take Jordan Nichols, a Kaska dene stone sculptor who is a member of the Indigenous Performing Arts Alliance (IPAA). He shares his name with an American television actor and model.

Because these two different artists have the same name, search engine robots may struggle to figure out which Jordan Nichols is being described on a particular webpage — especially when their artistic discipline isn’t specified. But with provenance metadata, we can explicitly tell these machines which pages talk about the Jordan Nichols from Edson, Alberta and which pages talk about the Jordan Nichols from St Louis, Missouri.

Because IPAA incorporates provenance metadata into their member profiles, search engine crawlers can understand that it is the Jordan Nichols from Edson, Alberta who is described in their member directory.

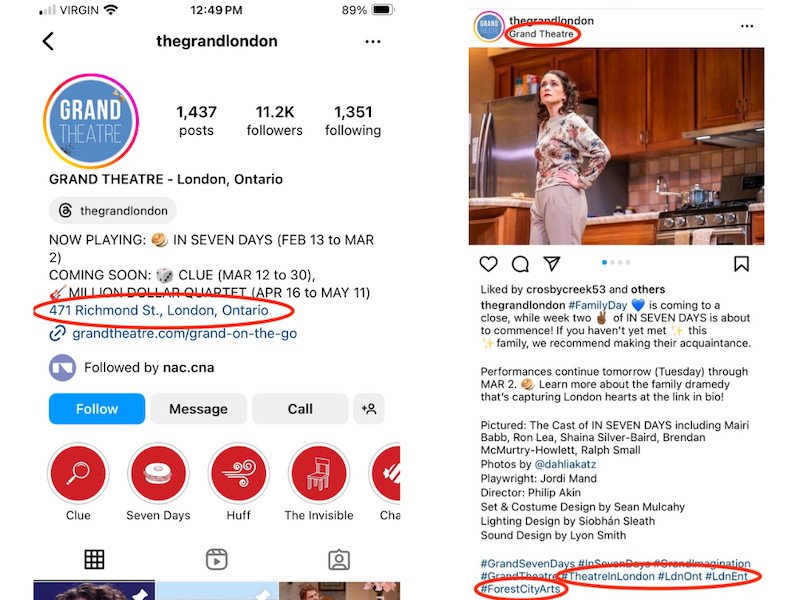

The same disambiguating process applies to other types of performing arts entities. After all, how many theatres called “The Grand” exist in Canada alone? Explicitly telling machines which webpages describe The Grand in Calgary vs. The Grand in Kingston Ontario vs. The Grand in London Ontario can therefore result in more accurate search results.

Making connections

Aside from telling machines “this person is not the same as this other person with the same name”, provenance metadata can work in the opposite direction. It can help confirm that two or more online resources do indeed talk about the same person. Better yet, even if one resource is lacking a given piece of provenance metadata, the other resource can supply that information through linked open data.

Let’s look at Sonia Johnson, a jazz singer/songwriter. She has an item (aka an entry) on Wikidata stating that her work location is “Canada”. This same item also has a link to her Spotify page, letting robots (and humans) know that these two Sonia Johnsons are one and the same.

Now, Spotify does not publicly release artists’ work locations, nor does it display a link to the artists’ Wikidata items. Nonetheless, through the Spotify ID link on Wikidata, we can explicitly tell machines that the Sonia Johnson on that Spotify page is the same person as the Sonia Johnson on that Wikidata item, who is based in Canada. Therefore, the Sonia Johnson on that Spotify page is also based in Canada.

These geographical statements may prove particularly helpful for location-based algorithms that are tasked to recommend Canadian content to internet users.

Getting started

As mentioned previously, Wikidata is an effective (and free!) means of creating provenance metadata about various performing arts entities. It also allows you to link that information to other online sources, such as websites, social media, and other databases (including OpenStreetMap).

- The Wikidata Media Library – video recordings and slideshows from our previous Wikidata workshops

- Tapping into the Open Data Pipeline (slides 29-33) – provenance properties in Wikidata for artists, creative works, organizations and venues

- Raising an Artist Profile in Wikidata (slides 35-36) – additional provenance properties in Wikidata for artists

- Indigenous Artists and Wikidata (pages 8-16) – Indigenous identities and provenance properties for Indigenous artists and their works

- A Hands-On Introduction to Wikidata (slides 40-47) – linking geographical coordinates on OpenStreetMap to venue items in Wikidata (and vice versa)

On your own website, you can add provenance information through Schema structured data. This type of metadata isn’t visible to human eyes, but explicitly tells robots exactly what kind of information is on a webpage. There are many structured data templates available online –– including one developed by the Artsdata team specifically for artists!

- Structured Data Templates for Artists – available in JSON-LD and Microdata formats

- Web code tools –– includes interactive structured data templates for organizations and other entities

Social media and other content creation platforms allow you to add varying degrees of provenance information –– not all of which is accessible as linked open data. Still, populating whatever data fields are available and adding relevant location tags and hashtags can help you stand out in location-specific search queries.

Obtaining consent

If you intend to publish provenance metadata on behalf of an artist other than yourself, check in with them first. Explain why provenance metadata is important (don’t hesitate to reference this blog post if needed). Tell them what particular kinds of metadata you are proposing to publish, and give them options to disclose at different levels of granularity. When provided with some context and given options, most artists will gladly consent to disclosing some provenance metadata.

If you have any questions about adding provenance metadata about yourself, your organization, your venue and/or the artists you represent, please send us an email at ldf.anl@capacoa.

About the Linked Digital Future Initiative and the Artsdata Project

From 2018 to 2023, the Linked Digital Future Initiative deployed a range of research, prototyping and digital literacy activities to foster discoverability, digital collaboration and digital transformation in the performing arts. Since 2023, the LDFI has gradually given way to the Artsdata Linked Open Data Ecosystem project. As the name suggests, the Artsdata project pursues the same vision of an ecosystem where multiple collaborators enable the free circulation of performing arts data.

This project is funded by the Government of Canada and by the Canada Council for the Arts.

CC BY 4.0

CC BY 4.0

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!