The COVID-19 pandemic has caused the most profound economic, social and human crisis ever experienced in the arts, culture and heritage sector. The performing arts sector – whose modes of production and dissemination rely heavily on gatherings and social proximity – is profoundly affected.

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, many arts service organizations and industry associations have surveyed their members to assess the impact of the crisis. Yet, even though thousands of organizations and cultural workers have been reporting on cancellations and lost gigs, we are still nowhere near to having a complete and accurate overview of the situation. Why is that? Because very few of these surveys are designed with the intent of contributing to painting the full picture. Most industry-led surveys are fraught with limitations that prevent data aggregation (assembling more of the same data) and data integration (connecting data about different things). Among other things, few are collecting data points that can serve as unique identifiers. Without reliable event or production identifiers, a single typo difference makes it impossible to automatically retrieve duplicates in datasets. In this context, how can one assert that cancelled performances reported by producing companies, touring agents and presenting organizations aren’t in fact the same events?

How can we give more value to our industry data about events, productions and organizations? And how can this value benefit all stakeholders of the performing arts value value chain?

Better surveying in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, could involve four things:

- Flexible privacy policies that enable data reuse;

- Common classifications for survey respondents (for example, standard industry or occupation classifications or else other classifications denoting aspects of diversity);

- Common impact indicators for each class of organizations or cultural workers;

- Unique identifiers to match individual answers from different surveys (in the absence of a global unique ID, an organization’s official website URL can serve as an identifier).

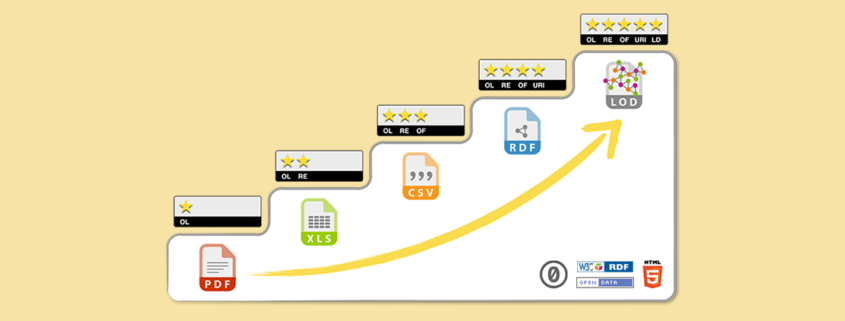

Interestingly, these are the precisely the kind of tools that the sector has been attempting to develop as part of digital transformation initiatives:

- Data mutualization strategies;

- Ontologies and conceptual models with standard classes and properties.

- Unique persistent IDs, Unique Resources Identifiers.

So? What can we do now? It would be arduous to retroactively attribute identifiers or to retroactively seek consent from survey respondents to share their individual answers. But, from now on, we can choose to work collaboratively to design and implement better data collection practices. If arts and culture are indeed a public good worthy of support from all levels of governments, perhaps is it time to start thinking about our industry data as an asset that can be leveraged for the public good. If not now, then when?

CC 4.0 BY-SA

CC 4.0 BY-SA

CC 4.0 BY-SA

CC 4.0 BY-SA

Since the publication of this post, I have been working with Synapse C and other arts service organizations to develop a COVID-19 impact assessment framework. It covers aspects such as privacy policies, identifiers, standard classifications and common indicators. Even though this is still just a working document, anyone is welcome to use it or comment it.